A year later: Iranian nuclear talks go from promise to doubt

Hassan Rouhani won world leaders’ warm embrace a year ago when he arrived at the United Nations General Assembly in New York as Iran’s new president, speaking of reconciliation and offering a new era in relations between his nation and the West.

But when Rouhani arrives next week for this year’s U.N. session, diplomats will be pondering a different question: What went wrong?

A year after that auspicious beginning, tensions with the West are as high as ever, and 10 months of negotiations over the toughest issue in the relationship — Iran’s nuclear program — are at an impasse. Now Western leaders want to know Iran’s intentions and if Rouhani is even calling the shots in Tehran on the nuclear issue and overall foreign policy.

Since November, when Rouhani’s team signed an interim nuclear accord that seemed to promise a breakthrough, “we’ve actually gotten further away from a deal,” said one Middle Eastern diplomat who spoke on condition of anonymity in discussing sensitive diplomacy.

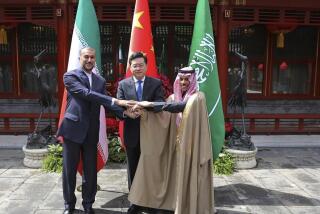

Negotiators from Iran and six world powers — Britain, China, France, Germany, Russia and the United States — will meet Friday in New York in an effort to break the logjam and complete a deal before the Nov. 24 deadline. Next week, foreign ministers from the nations will take up the issue.

Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, declared last year that he was giving his full support to Rouhani to negotiate a nuclear deal that would ease international economic sanctions on Iran in exchange for commitments to keep its nuclear program peaceful.

But in recent months, signs suggest the staunchly anti-Western Khamenei is directly managing the negotiations. He appears determined to sharply increase the country’s uranium enrichment capability in seven years, and not roll it back, as the West demands.

Rouhani, who has lost a series of domestic political battles to conservatives, has taken a harder line on the nuclear talks. In a news conference two weeks ago, he expressed doubt that the U.S. has enough “goodwill” to negotiate an end to the standoff.

In an indication of the changing mood, President Obama plans no contact with Rouhani during the U.N. session, according to White House aides. Last year, the two leaders spoke by phone while in New York, the highest-level contact between the two countries in decades.

The central question for diplomats is whether Iran’s tougher line is only negotiating theatrics, aimed at gaining better terms, or whether Khamenei has decided he can survive a collapse of the talks despite Western threats of tighter sanctions.

Increasing evidence suggests Khamenei believes he can get by without a deal, say diplomats and analysts.

In recent comments, Khamenei portrayed the U.S. as beset by crises, including the standoff with Russia over Ukraine and the conflict with Islamic State militants in Syria and Iraq. He may view American efforts to solicit Iran’s cooperation, at least on nonmilitary matters, in the fight against the militants as a sign of weakness.

At the same time, the conservative Iranian Revolutionary Guard, which is hostile to a deal, is wielding greater public influence because of fears of the Islamic State threat.

Many Western analysts argue that if negotiations fail to produce a deal, U.S and European sanctions would intensify, not collapse, choking off much of Iran’s sales of 1.2 billion barrels of oil a day.

But Khamenei may believe that if the talks collapse, he could persuade Russia, China and perhaps other nations to abandon the sanctions and resume buying Iranian oil, providing the cash his government needs.

“Khamenei is preparing his country for a no-deal outcome,” said Cliff Kupchan, a former State Department official who is with the Eurasia Group risk consulting group.

Diplomats say they expect Iran will try to blame the U.S. during the U.N. sessions for the deadlock in talks, and will try to build support for ending sanctions and allowing Iran to maintain its nuclear infrastructure.

Wendy Sherman, the chief U.S. negotiator, predicted in a speech Tuesday that Iran would try to convince the world that “the status quo, or its equivalent, should be acceptable.”

Gary Samore, Obama’s former top advisor on nuclear proliferation, said Khamenei “seems to be very stubborn and very confident that he can retain his enrichment capability.”

While the Iranian leader may be wrong, “what matters is what he believes,” said Samore, who is now with the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government.

Robert Einhorn, another former member of Obama’s inner circle on nuclear issues, said nuclear negotiators won’t be able to resolve complicated secondary issues by the Nov. 24 deadline unless they solve the bigger question of how much enrichment capability Iran can keep.

“They’re still light-years apart,” said Einhorn, now with the Brookings Institution.

Special correspondent Ramin Mostaghim in Tehran contributed to this report.

Follow @richtpau on Twitter

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.