The domestic and international tensions over the Obama administration-backed Iran deal flared at a town hall meeting on the subject Brooklyn Congressman Hakeem Jeffries held last night in Brighton Beach.

Perhaps a hundred people packed into a Jewish community center in the Brooklyn enclave, which is home to thousands of Russian-speaking emigres from the former Soviet Union, many of whom fled anti-Semitism in their native nations. The average age in the room was probably around 70 years old, and the deep ties the audience felt to Israel were on display on hats, t-shirts and homemade signs.

Mr. Jeffries, a black Democrat with a large Jewish constituency, repeatedly stressed that he had not yet decided how to vote on the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, an arrangement Secretary of State John Kerry helped broker that would relieve sanctions against the Islamic theocracy in exchange for a decade-long pause in its nuclear weapons program. The congressman reiterated arguments for and against the plan, and said he was listening to residents of his district before deciding how he would vote on the agreement.

“Let me make clear, in my view, we have to do everything possible to ensure that Iran never acquires nuclear weapons capabilities,” he said, his voice drowned out for a moment in applause as he described the Middle Eastern nation’s role in supporting international terrorism. “We must do everything possible to prevent them from ever acquiring a nuclear bomb.”

He also warned against the dangers of sinking the United States into another prolonged military venture in the region, garnering a hand from the small caucus of supporters of the deal in the room. The situation he described was stark: Iran presently has 19,000 centrifuges for refining military-grade uranium, and could make a mad sprint toward a full-blown atomic weapon in a matter of months if the deal fails—yet he echoed concerns that the plan could permit the pariah state to make slow, secretive progress toward a nuclear arsenal without the United States being able to effectively re-impose the sanctions that have all but broken the Iranian economy.

On hand to explicate the latter viewpoint was Zachary Goldman, executive director of the Center on Law and Security at New York University.

“We give up the most powerful sanctions regime in history. And it was the sanctions that everybody more or less agrees brought Iran to the table,” Mr. Goldman said. “The deal does not address Iran’s atrocious human rights record, the deal does not address Iran’s support for terrorism.”

“The ability to re-impose sanctions in the event of an Iranian violation appears in the deal to be an all-or-nothing proposition. Meaning we can only fully re-impose sanctions or do nothing at all,” he continued. “With this, the fear is what that incentivizes Iran to do is to violate the deal a little bit at a time, in which each little violation probably isn’t significant enough on its own to justify a full re-imposition of sanctions, but when accumulated over time will effectively allow Iran to wiggle out of its commitments.”

Former State Department official Joel Rubin flew in from Washington, D.C.—and arrived 45 minutes late—to defend the administration’s stance. He appeared to treat a nuclear Iran as an inevitability that can only be postponed.

“There is only one country in the world that can stop Iran from getting a bomb, and that’s Iran. Only Iran can decide not to make the bomb. We can’t bomb them into a place where they won’t make it,” he argued, amid heckling from the audience. “Would you rather have them have a nuclear weapon in a few months or in 10 to 15 years?”

The congressman then took comments from several dozen members of the audience, who—except for two—were universally opposed to the deal.

Mr. Rubin became the target for much of the audience’s anger, with one woman comparing him to a group of Jewish people who she claimed marched in Manhattan in support of Adolf Hitler. Others exclaimed in Russian that the deal would lead to the nuclear obliteration of Israel.

“No president has ever been more committed to Israel’s security than President Obama,” Mr. Rubin said, to almost deafening boos.

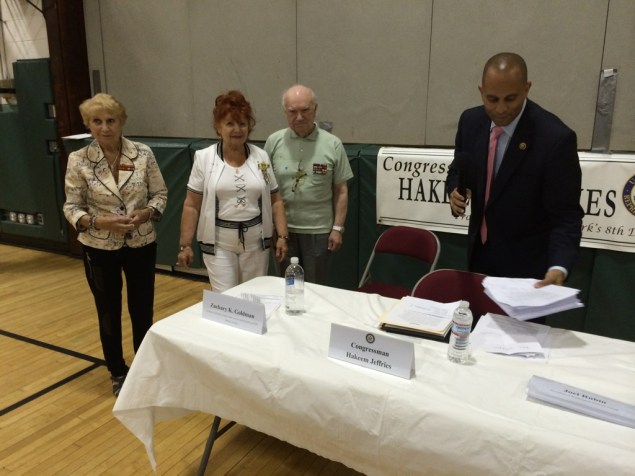

Two Soviet World War II veterans, Anastasia Braverman and Boris Feldman, presented to Mr. Jeffries a sheaf of 300 signatures from people in the neighborhood calling on Mr. Jeffries to vote no on the plan—petitions they claim to have collected in just two hours earlier in the day. The congressman promised he would not forget past world events.

“The decision Congress is going to have to make will be made in the context of history, and there’s no more invidious historical event than the event that took place as it relates to the Holocaust,” Mr. Jeffries said, recalling his visits to Israel in office. “When someone says they want to annihilate you and wipe you off the face of the earth, we should believe them. Because it happened before.”

New York’s senators have split on the plan, with junior Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand supporting the deal and senior Sen. Charles Schumer opposing. Congresswoman Grace Meng of Queens and Congressman Eliot Engel of the Bronx, as well as Long Island representatives Steve Israel and Kathleen Rice, are among the New York Democrats to announce their opposition to the plan.

Congress may vote against the agreement, but Mr. Obama will have the power to veto their decision, and most observers agree that opponents will not be able to pull together enough members to override the veto.

Mr. Jeffries is seen as a rising political star in New York City, and rumors abound that he aims to challenge Mayor Bill de Blasio in the Democratic primary in 2017.