Editor’s Note: Professor Ali Ansari is director of the Institute for Iranian Studies at the University of St. Andrews.

Story highlights

Iranian regime is keen to encourage the public to put the past behind them, Ali Ansari writes

He points out the consolidation of power around Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei

Ansari: Khamenei has been able to blame divisions on Ahmadinejad and his "deviant current"

Former President Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani’s abrupt fall from grace has taken many in political circles in Iran by surprise, further widening the gap between an increasingly insular and narrow hard-line elite and the rest of the country.

It reinforces a trend towards the consolidation of power around Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and his acolytes, which has been taking place for the better part of a decade, and perhaps the real surprise is the fact is that there remain members of the elite who did not think this remorseless process would ultimately apply to them.

Ever since the political catastrophe of 2009, when millions pored onto the streets to protest what was widely considered to be a highly fraudulent election process, the regime has been keen to encourage the public to put the past behind them and to look forward to these elections as a cathartic exercise during which political blemishes could be washed away.

Rafsanjani’s dramatic last-minute entrance into the race, was seen by many as proof that some lessons had indeed been learnt.

But if Rafsanjani was to galvanize the public, then his platform had to be radical and his boast that he had come to “save the nation” and effectively “reboot” the Islamic Republic, was certainly bold.

However, the fact that he claimed that he had to ask permission to run, was indicative of how far the political realities of Iran had changed since he had last been president (1989-1997).

No sooner had he registered than the bitter personal attacks came from the hard-liners; while others questioned just what the nature of the agreement with Khamenei had been, if any.

Amanpour explains: Iran’s presidential election

But perhaps most galling was that for all the hype and excitement generated by his supporters, the public appeared unmoved.

Popular momentum might have developed, though the task would have been considerably harder than 2009 given the absence of a political infrastructure of street activists, (largely dismantled since 2009), and above all the sheer cynicism of the voting public.

Public apathy combined with the conceit of the new ruling class, to deliver a particularly brutal humiliation to Rafsanjani, barred apparently not for his political views, but for the rather less dignified reason that the members of the Guardian Council thought Rafsanjani too old to be able to bear the burden of office.

Rafsanjani’s dramatic entrance and precipitous fall has shone a light on the growing fractures within elite politics in Iran. To date Khamenei has been able to blame divisions on Ahmadinejad and his “deviant current” on the one hand, and the foreign inspired sedition of Mir-Hussein Musavi and Mehdi Karrubi (still under house arrest) on the other.

Few expected Ahmadinejad’s protégé, Esfandyar Rahim Mashaie, to survive the vetting process – other that is, than Ahmadinejad, for whom being on the “outside” must be an uncomfortable experience.

Similarly, if slightly more realistically, few of Rafsanjani’s supporters considered him vulnerable. He remained after all a pillar of the establishment, even if two of his children had been hounded into jail and he had effectively been ostracized over the past four years for his tentative support of the Green Movement.

Read more: How the U.S. should respond to Iran’s election

It says much of the “wishful thinking” that remains prevalent, that they thought this a political virtue.

Firm in the belief that the Islamic Republic faced an existential threat, they had retained their faith in the integrity of a system that has long since transformed beyond recognition into a sacred autocracy.

Indeed the unpredictability of the Iranian political system is not a reflection of its inherent ‘democracy’, but of the absence of the rule of law and the growing identification of power in the person of Khamenei.

Both the Guardian Council’s “rulings” (which it should be stressed are neither published nor explained) and the fact they can be overturned on the whims of the Supreme Leader, are indicative of this harsh reality.

What we are left with is a tightly controlled “election” with a dry and uninteresting field. Of the eight ratified candidates, one is a nonentity, (Mohammad Gharazi); two are ostensible “moderates” lacking in charisma and therefore non-threatening, (Hassan Rouhani and Mohammad Reza Aref); one is an independent Principle-ist (Mohsen Rezaei) who likes to speak his mind but on past performance is unlikely to garner votes (real or imagined); while the remaining four are self proclaimed acolytes of the Leader.

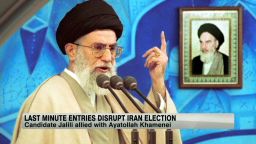

Of these four, two have been highlighted as the probable annointees: Saeed Jalili, the current head of the National Security Council, and Mohammad Ghalibaf, the mayor of Tehran.

Jalili is widely assumed to be the favorite and his web presence is suitably polished and indicative of considerable preparation, though quite who the audience for this is, given the current restrictions on internet access in the run-up to the election, remains unclear.

Jalili is perhaps closest ideologically to the Supreme Leader. For this particular puritan, the crisis Iran faces is not existential, it is an opportunity to be seized and a trial to be welcomed.

Ghalibaf, who once fancied himself as Iran’s answer to Tom Cruise, has had his popular credibility bruised by the sudden release of a recording of a speech he allegedly gave to members of the Basij militia bragging about how much he enjoyed getting on his motorbike and thumping students.

Ghalibaf has vigorously dismissed the recording as a malicious smear, but it says much about current politics that there are many who find it credible.

The real question of course is the source of the leak; and herein perhaps lies the real significance of recent developments. In 2009, the regime lost the people; it now appears to be in the process of divesting itself of its traditional elite. How the newly disenfranchised react will be interesting to watch. This may be the real legacy of the “election” of 2013.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Ali Ansari.